| URLs in this document have been updated. Links enclosed in {curly brackets} have been changed. If a replacement link was located, the new URL was added and the link is active; if a new site could not be identified, the broken link was removed. |

How to Read Scientific Research Articles: A Hands-On Classroom Exercise

Science Instruction Librarian

University of Texas

Austin, Texas

roxanne.bogucka@austin.utexas.edu

Reference/Instruction Librarian

Pierce College Fort Steilacoom

Lakewood, Washington

ewood@pierce.ctc.edu

Abstract

Undergraduate students are generally unfamiliar with scientific literature. Further, students experience frustration when they read research articles the way they read textbooks, from beginning to end. Using a team-based active learning exercise, an instruction librarian and colleagues at University of Texas at Austin introduce nutritional sciences students to a method for reading research papers. Librarians provide student-pairs with one section (introduction, methods, results, or discussion) of a scientific research article. Student-pairs read, discuss, and take notes, then join with pairs assigned the other sections of the article to compare their understanding of the research presented. The exercise reinforces students' critical evaluation skills by providing a productive reading strategy based on the purpose of each section of the research article. This paper describes the active learning exercise and discusses its implementation and evolution.

Introduction

In the fall semester of 2007, Roxanne started teaching three library instruction sessions for an upper-division nutritional sciences course with a significant writing component. The class typically has between 20 and 30 students. Students in the course identify, read, analyze, write about, and present scientific research on selected topics in nutrition and human health. The class is structured as a journal club, with two major assignments -- a favorite paper presentation and a literature review presentation. For the favorite paper assignment, students send a research article of their choice to their classmates, who prepare two questions for the presenter to address on the day he or she discusses the selected article. Students similarly receive and submit questions on classmates' literature reviews, which student reviewers address during their scheduled presentations.

The instructor wanted students to learn how to search PubMed, how to read and evaluate the articles they found in their searches, and how to cite these articles, preferably via hands-on exercises.

The sessions incorporated active learning. Active learning is a method of teaching that brings students into the process of their own education through discovery and participation (Lorenzen 2001; Grassian & Kaplowitz 2001), and often involves a social aspect, such as collaboration among peers (McGill 2004). Active learning methods have been used for some time in library instruction, especially in health sciences library instruction (Francis & Kelly 1997; Fosmire & Macklin 2002) but can be challenging for librarians to practice when their exposure to students is limited to one session and they have much material to cover (Drueke 1992). Since Roxanne was meeting with the class for three instruction sessions, we could build upon what students had learned during and in between the earlier instruction sessions and devote more time to active learning exercises.

It was easy enough to conceive what a hands-on session on PubMed or EndNoteTM would look like, but creating a how-to-read exercise took more investigation. Searches on reading scientific articles uncovered several works that describe the typical sections of a research article and their contents, plus a few recommended reading methods. Leedy (1981) advises tackling an article straight through, but re-reading the problem statement immediately after finishing the discussion section to see whether the conclusions are congruent with the question posed. Polit (2010) recommends skimming and a close re-read, followed by writing a synopsis. Gehlbach (1993) advises busy clinicians to save time by reading an article's Methods section first, since any Discussion or Conclusions arising from unsound methodology would be of dubious value. While he has a point, a Methods-first approach is too challenging for our population -- novice users of scientific research.

Greenhalgh (2003) notes two challenges novice users face in understanding scientific literature -- inability to select the right types of articles for an information need and a lack of strategy for effectively reading the articles. These two skills -- evaluation and critical reading -- informed the learning outcomes for our information literacy session.

Searching for tutorials led to an excellent Flash animation from the Purdue University Libraries, "How to Read a Scientific Paper," and a useful note-taking form for reading scientific articles (Purugganan & Hewitt 2004), which was adapted for use in the nutritional sciences class. Repeat viewings of the Purdue tutorial led Roxanne to wonder what readers would learn about an article if they had only one section of it. Once that question arose, the article-reading exercise practically planned itself. In the spring of 2009, the authors co-taught the how-to-read session.

Materials Needed

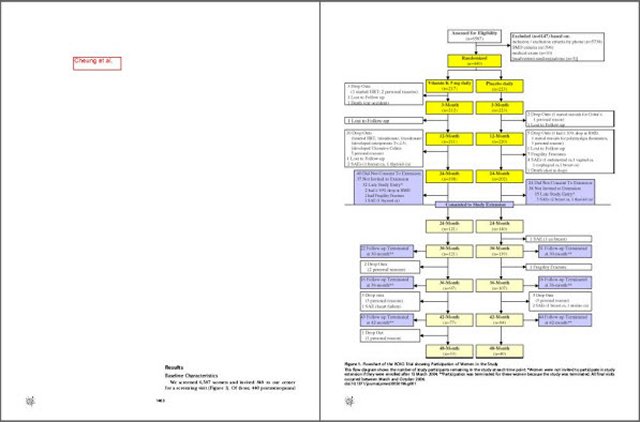

For the main portion of this exercise, we selected three or four research articles, to produce 12 or16 article sections. We generated the article sections (Figure 1) by:

- locating a PDF of the article

- concealing or effacing the article title and journal title from every page

- masking off sections of text so that the only text, figures, and tables visible are those that belong in a particular section (introduction, materials and methods, data/results, discussion/conclusions) of the paper. (You can do this rather tediously, using paper and a photocopier, or rather easily using Adobe Acrobat's Redaction feature if you have access to it)

- labeling each article section with the name of the first author

- printing out each complete article, plus each article's four masked sections

Figure 1. Sections of Cheung et al. 2008: a) introduction b) methods c) results d) discussion

In addition, we created a folder in Academic Search Complete that contained:

- a link to full-text of a research article with IMRaD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) (Polit 2010) structure

- a link to full text of a review article

- database records with abstracts for at least three research articles and an equal number of review articles

We supplied note-taking forms for the students. It helped that chairs and desks could be shifted around into small discussion groupings in the classrooms used, but the exercise can be managed in rooms with static furniture.

Description

The instruction session included several strategically placed active learning exercises designed to replicate the research process for the class's journal club assignment. At the end of the session we wanted students to

- analyze an article's structure and content in order to distinguish research articles from review articles

- analyze elements of a database record in search results in order to classify an article as research or review

- understand what information can be found in sections of a typical research article in order to read more efficiently

- apply knowledge of reference tools in order to increase comprehension of research articles

We began by having students talk about their previous experiences with scientific articles. Students were asked to describe common elements in the structure of the articles they'd seen. We showed students an IMRaD-format research article and a review article and drew them into a discussion of the structural differences between research articles and review articles. To check understanding, we displayed the full text of other research articles and review articles and had students distinguish between the two based on their structure.

Once students were able to distinguish between research and review articles, we moved on to the abstract. For this assignment, students needed to find and present on research articles. We wanted students to be able to determine quickly whether search results in a database were research or review articles, and to be able to decide whether a given research article was worth their time based on the information conveyed in the abstract.

From the folder we set up in Academic Search Complete, we displayed database records with abstracts for several scientific articles. Working as a class, students analyzed the language used in the abstract and/or title, to determine whether an article presented original research or reviewed the current state of research. From this activity the students identified textual cues to help them learn to recognize abstracts for research articles.

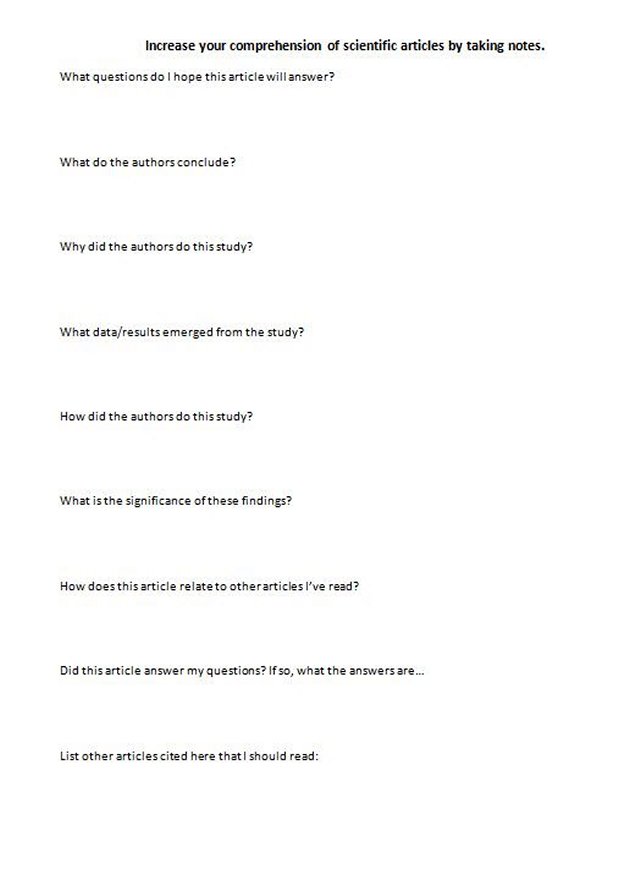

With this basic understanding established, we moved to the research article reading exercise. We asked students to work in pairs but depending on the size of the class and the day's attendance, some students occasionally had to work as solos or in threes. Each pair received an article section and a note-taking form (Figure 2).We took care to avoid giving adjacent pairs sections from the same article. Student pairs were allowed 10 minutes to read their sections and take notes. Since we needed to re-use the article sections in a later class, we asked students not to highlight their article section or write on it, but to use the note-taking form instead.

Figure 2. Note-taking form (adapted from Purugganan & Hewitt 2004)

We circulated through the classroom during this time, listening to students' discussions of their article sections. When the 10 minutes were up, we asked for a show of hands for all pairs that read sections labeled Author A, Author B, Author C, etc., and had pairs move to sit with the others who had read sections of the same article. Student pairs were then given eight minutes to report out within their groups, in this order: 1st, Methods pair; 2nd, Results pair; 3rd, Introduction pair; 4th, Discussion pair. During the reporting phase we circulated throughout the classroom, listening to the reports, glancing at note-taking forms, and asking questions as needed to elicit students' comments on the relative comprehensibility of their particular article sections.

Though there was of course some variation, in most groups the pair who read the Discussion section was most able to answer questions on the note-taking form. Typically Discussion and Introduction pairs knew the most about the research presented, while Methods pairs and Results pairs had the least understanding of what their article was about. By having students share their differences in information and understanding, based on which section of the article they read, this exercise demonstrates the value of the reading method we recommend for them, ADIR(M) -- Abstract, Discussion, Introduction, Results, (Methods).

Step 1: Abstract. Although it is not part of the reading exercise, we tell students to start here and ask, "Is this article relevant enough to proceed to the full text, or should I move on to another article?"

Step 2: Discussion. Ask "What are the researchers' findings?"

Step 3: Introduction. Ask "Why did the researchers do this study?" and "Does the research question match up with the conclusions I read in Step 2?"

Step 4: Results. Ask "Are the data collected appropriate to answer the research question?" and "Do the data support the conclusions?"

Step 5: Methods (optional). Ask "How can I repeat this study?" and "Are these methods suitable to gather the results reported?"

To close the instruction session we encouraged students to use online reference sources as they read articles, to look up unfamiliar terms, concepts, and methods. We modeled this process by taking a term from a research article we had used earlier in the session and searching for it in Gale Virtual Reference Library. The students also were shown how to find e-book dictionaries in the library catalog and where to access additional tips on research articles on the library web site.

Assessment

Our assessment of the effectiveness of these instruction sessions has been strictly informal, through discussions with the course instructor and a teaching assistant, and through comments from students. The course instructor appreciated that this instruction session mirrored, on small scale, tasks required for the course's major assignments, the favorite paper presentation and the literature review presentation. The instructor also reported that students show a better grasp of the material, which she attributes to their ability to search for and efficiently read scientific articles. She observed that the session significantly reduced students' apprehension surrounding the scientific literature research process and said that after this session students reported that they felt more confident about their research abilities. In recent course evaluations the instructor has scored highly when students are asked if the "Instructor has increased my knowledge and competence in this course." She attributes this response to this collaboration with librarians for information literacy instruction.

Conclusion

Overall, students respond positively to the how-to-read exercise because it quickly shows them that some scientific article sections reveal more than others. After the active learning exercise students seem more receptive to the reading method we suggest. This hands-on exercise will continue to evolve, based on feedback from course instructors and teaching assistants, as well as from students.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Michele Ostrow and Robyn Rosenberg for their comments on this article.

References

Badke, W.B. 2000. Research Strategies: Finding Your Way through the Information Fog. San Jose, Calif.: Writers Club Press.

Cheung, A.M., et al. 2008. Vitamin K supplementation in postmenopausal women with osteopenia (ECKO Trial): a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Medicine 5(10):1461-1472. [Online]. Available: http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.0050196 [Accessed: December 2, 2009].

Davies, B. & Logan, J. 2008. Reading Research: A User-Friendly Guide for Nurses and Other Health Professionals. Toronto: Mosby Elsevier.

Drueke, J. 1992. Active learning in the university library instruction classroom. Research Strategies 10(2):77-83.

Fosmire, M. and Macklin A. 2002. Riding the active learning wave: problem-based learning as a catalyst for creating faculty-librarian instructional partnerships. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship. [Online]. Available: http://www.istl.org/02-spring/article2.html [Accessed: June 12, 2009].

Francis, B. & Kelly, J. 1997. Active learning: its role in health sciences libraries. Medical Reference Services Quarterly 16(1):25-37.

Gehlbach, S.H. 1993. Interpreting the Medical Literature. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Grassian E.S. & Kaplowitz, J.R. 2001. Information Literacy Instruction. New York: Neal Schuman.

Greenhalgh T. 2001. How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence Based Medicine. London: BMJ Books.

How to read a scientific paper. West Lafayette (IN): Purdue University Libraries. [Online]. Available: {https://www.lib.purdue.edu/help/tutorials/scientific-paper} [Accessed: June 30, 2009].

Leedy, P.D. 1981. How to Read Research and Understand It. New York: Macmillan.

Lorenzen, M. 2001. Active learning and library instruction. Illinois Libraries 83(2):19-24

McGill, I. 2004. The Action Learning Handbook. New York: Routledge Falmer.

Machi, L.A. & McEvoy, B.T. 2009. The Literature Review. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Polit, D.F. & Beck, C.T. 2010. Essentials of Nursing Research: Methods, Appraisal, and Utilization. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Puruggannan, M. & Hewitt, J. 2004. How to Read a Scientific Article. Houston (TX): Rice University. Cain Project for Engineering and Professional Communication. [Online]. Available: http://www.owlnet.rice.edu/~cainproj/courses/HowToReadSciArticle.pdf [Accessed: June 30, 2009].

| Previous | Contents | Next |