What I've Been Reading

The Next Generation Science Standards and You

Michael Fosmire

Head, Physical Sciences, Engineering, and Technology Division

Purdue University Libraries

West Lafayette, Indiana

fosmire@purdue.edu

Those of us who have been holed up in the academy for the past several years sometimes lose touch with innovations that happen in the rest of the educational world. One of the major initiatives in K-12 education in the past few years was the development of the Common Core State Standards. Often, we became aware of the CCSS when several states, including my own, decided it was too centralized and trampled on their sovereignty. Despite all the political back and forth, the CCSS, and in particular for us as sci-tech librarians, the Next Generation Science Standards, have been a watershed of change in approach to learning and something academic librarians ignore at our peril. As students exposed to the NGSS pedagogies and outcomes start entering institutions of higher education, it behooves us to understand where students are coming from and what they should be expected to know as a basis for scaffolding our own goals for student learning.

Maybe it would be best to rewind the clock to the turn of the century to peer a little way into the history of K-12 and higher education standard development. In 1998 the American Association of School Librarians introduced Information Literacy Standards for Student Learning (AASL and AECT 1998). Shortly after the adoption of the AASL Standards, ACRL created its own Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (ACRL 2000), which explicitly acknowledge that it "extends the work of the American Association of School Librarians Task Force on Information Literacy Standards, thereby providing higher education an opportunity to articulate its information literacy competencies with those of K-12 so that a continuum of expectations develops for students at all levels." (p.5)

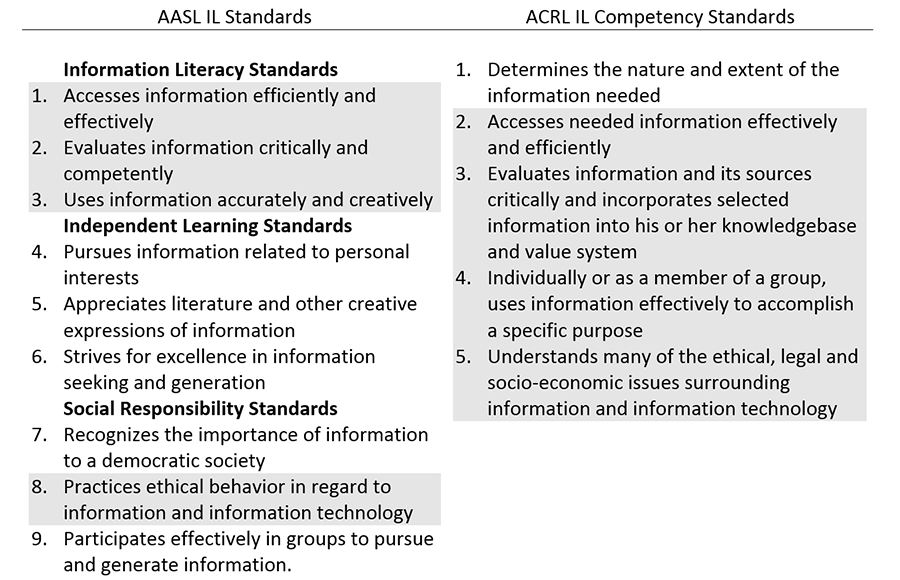

The AASL subdivided their standards into three categories, Information Literacy, Independent Learning, and Social Responsibility (see Table 1), the first of which relates most directly to classic library instruction, while the other two incorporate other learning concepts that have broad overlap with information literacy. The ACRL Competency Standards largely echo the AASL standards, with AASL standards 1, 2, and 3 corresponding to ACRL standards 2, 3, and 4. ACRL standard 5 corresponds to AASL standard 8, on ethical use of information, while ACRL standard 1 is encompassed, briefly, in AASL standard 1. However, the ACRL competency standards focus largely on objective, almost mechanistic, processes and not on affective facets or motivation, such as the AASL's "appreciates literature" or "pursues information related to personal interests." Essentially, ACRL focused on extending and deepening the Information Literacy batch of standards from AASL and didn't explicitly touch the Independent Learning and Social Responsibility standards.

Table 1: Comparison of AASL Information Literacy Standards for Student Learning (AASL and AECT 1998) and ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (ACRL 2000)

Fast forward to 2016, and the adoption of the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (ACRL 2015), which, again, followed the adoption by AASL of their Standards for the 21st Century Learner (2007). Each AASL standard is subdivided into Skills, Dispositions in Action, Responsibilities, and Self-Assessment Strategies, so that, in order for the students to be truly information literate they must not only have the appropriate skills, but must also want to use them, understand they need to be accountable to themselves for using those skills, and, finally, be reflective on their habits to improve their performance. Ratzer (2014) proclaims that the Standards for 21st century learners "are based on effective and motivational pedagogy that is brain-based and inquiry-driven."

In the development of the Framework, "the new AASL standards helped ACRL librarians rethink their stance on the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that post-secondary students should develop and achieve by the time they graduate" (Farmer 2014, p.2). Farmer notes that in the AASL standards, "'information literacy' occurs in just one paragraph, noting only that it has become more complex 'multiple literacies, including digital, visual, textual, and technological, have now joined information literacy as crucial skills for this century.'" Similarly, the Framework "draws significantly upon the concept of metaliteracy, which offers a renewed vision of information literacy as an overarching set of abilities in which students are consumers and creators of information who can participate successfully in collaborative spaces...with special focus on metacognition, or critical self-reflection, as crucial to becoming more self-directed" (ACRL 2015, p.2). The Framework also acknowledges the affective domain through its enumeration of Dispositions, in addition to Knowledge Practices.

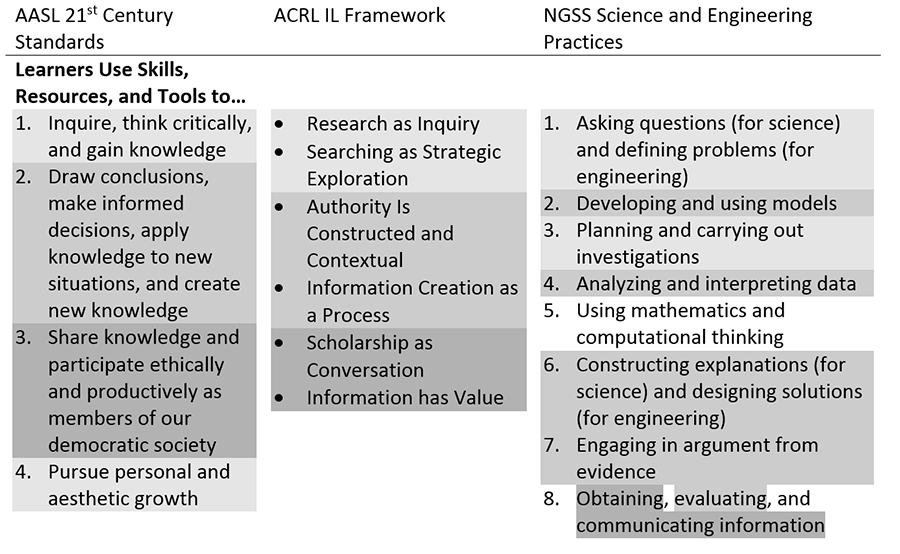

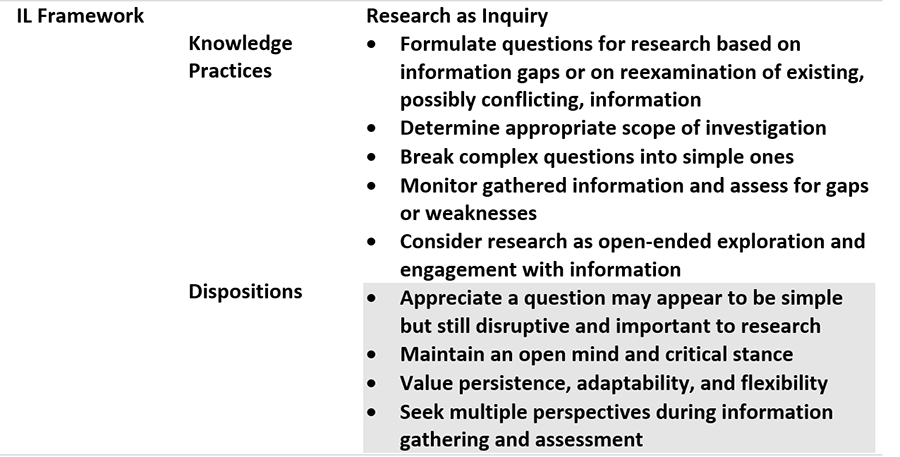

In this respect the ACRL Framework embraces a broader scope of affective and reflective components than the original Competency Standards, more commensurate with the AASL standards, while departing from a standards perspective to a framework/threshold concept approach. As such, specific outcomes are embedded in the Knowledge Practices and Dispositions. Nonetheless, the Frames in the Framework can loosely be grouped into Searching (Searching as Strategic Exploration, Research as Inquiry), Evaluating (Authority is Constructed and Contextual, Information Creation as a Process), and Ethical Use (Research has Value, Scholarship as Conversation). Thus, one could correlate the AASL and ACRL models, very roughly, as indicated by the shading in Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of AASL Standards for 21st Century Learners (AASL 2007) to ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (ACRL 2015), and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) Science and Engineering Practices (NGSS Lead States 2013). Shaded standards indicate common concepts across the documents.

All this provides context for how higher education and K-12 libraries have interacted over the years, with the goal of building on skills and dispositions developed in K-12 to scaffold the next level of complexity expected of college students. But, how does this impact the STEM librarian? Circling back to the Next Generation Science Standards, which are based, incidentally, on A Framework for K-12 Science Education (NRC 2012), the American Association of School Librarians' Standards for the 21st Century Learner already align well with the CCSS and NGSS and provide a road map for how information literacy integrates extensively with the core standards. AASL provides several crosswalks between these standards, including one for NGSS, broken down by grade level and subject area (AASL 2015).

As those crosswalks run over a hundred pages, covering every topic individually, I prefer to look at the bigger picture. The NGSS, which like the AASL standards, springs from an inquiry-based model of learning, can be divided along three dimensions, Science and Engineering Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Disciplinary Core Ideas. I believe, most relevant for librarians are the eight Science and Engineering Practices (see Table 2, Column 3), as they focus on the ways students achieve the content standards embedded along the other two dimensions. Just as information literacy practices can be written in a disciplinary neutral form, the Science and Engineering Practices delineate processes rather than content requirements. All three documents provide a matrix-like, multidimensional approach to standards, allowing for connections and multiple points of entry for the standards.

There is the obvious inclusion of the "obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information," Science and Engineering Practice, which would seem to cover everything for librarians. It is certainly gratifying to see information gathering front and center in the NGSS, and offers a great entry point for librarians to make the case for integration with the science classroom. However, as we all know, the power of information literacy is in how it is embedded in a curriculum, not as a stand-alone, dare we say, 'one-shot.' Indeed the NGSS embraces this integrated thinking about the Practices, indicating that "the eight practices are not separate; they intentionally overlap and interconnect" (NGSS 2013, p.3). Thus, we should look further at how the other NGSS Practices incorporate information literacy concepts, for seamless integration, and consider the spectrum of development from AASL standards through the Framework frames.

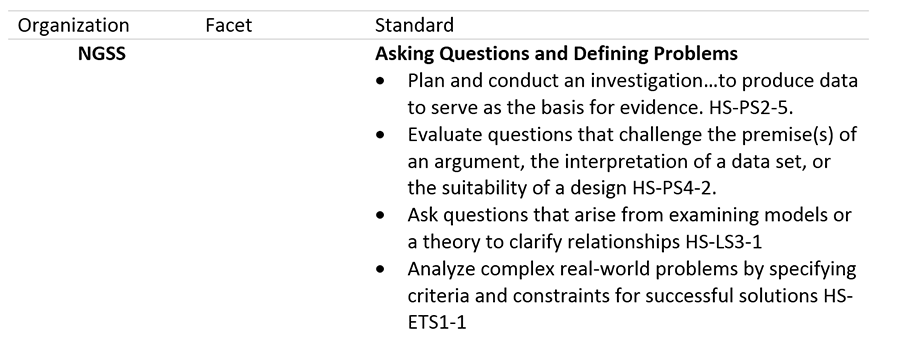

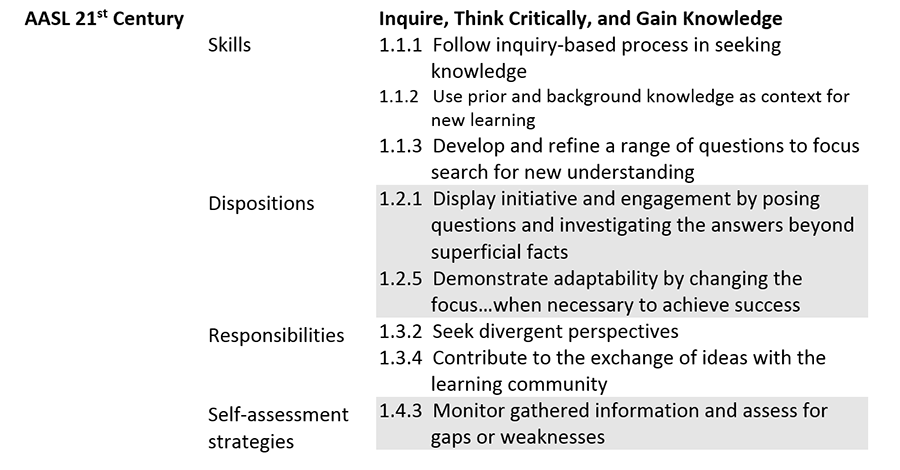

As the AASL Standards and the IL Framework each have 83 Skills, Dispositions, Responsibilities, and Self-Assessment Strategies; and Knowledge Practices and Dispositions, respectively, I could spend pages creating crosswalks and maps between the documents and the NGSS, as AASL has already done, as mentioned above. Let me just look at one facet of each (see Table 3) to show how AASL, ACRL, and NGSS standards interrelate. The NGSS high school standards in Physical Sciences (PS), Life Sciences (LS), and Engineering Design (ETS) have content standards, but also reference the Science and Engineering Practices embedded in those standards. Thus, two Physical Science standards, a Life Science and an Engineering Design standard have Science and Engineering Practices outcomes associated with Asking Questions and Defining Problems. Comparing those Practices just for the AASL standard 1, Inquiring, Thinking Critically, and Gaining Knowledge, and the ACRL Frame of Research as Inquiry, one can see that the information literacy standards/frames provide much more depth to flesh out how students might carry out the NGSS standards.

Thus, "evaluating questions that challenge the premise(s) of an argument" would utilize AASL skills such as "following an inquiry-based process for seeking knowledge" and using "prior and background knowledge as context." The IL Framework prompts students to, for example, "formulate questions for research based on information gaps or on reexamination of existing, possibly conflicting, information" and to "break complex questions into simple ones." The Dispositions, Responsibilities, and Self-Assessment Strategies, similarly provide a roadmap for how questions can be asked and problems defined along mechanistic, cognitive, and affective domains.

Table 3: Crosswalk of NGSS High School Science and Engineering Practice 1, AASL Standards for the 21st Century Learner, and ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.

So, now what? It's great to see lots of tables of this and that, but what is one supposed to do with it? Well, this could be considered the Rosetta stone for interacting across the higher-education/K-12 and library/science-engineering divides. Contextualizing information literacy concepts in the language STEM educators are using will help drive common understanding and shared goals for actualizing effective, integrated instruction programs. In my own experiences with K-12 educators, particularly in recent years, there is always a bottom line in partnerships, "what standards will these activities address?" If one can't articulate a connection to the student learning outcomes required by the state, it is almost impossible to bring students in for activities on campus, or otherwise engage in activities to try to bridge the gap between high school and the first year of college. Now, when a STEM instructor asks about Practice 8, "Obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information," since we are, after all, the libraries, we can respond with, "what other practices are you engaging with in your activity," and describe the information literacy practices and dispositions that naturally dovetail with those practices. Instead of being an add-on, specific, relevant information literacy concepts can be embedded within the framework of the other activities the STEM instructor is carrying out.

From a research standpoint, Subramaniam (2015) sent school librarians a call to action to create, in the words of Todd (2008) 'evidence for practice, evidence in practice, and evidence of practice,' looking at three different components of application of information literacy in NGSS: using research to inform the building of teaching practice, gathering data to identify learning needs and gaps, and demonstrating the effect of teaching on closing those achievement gaps. Subramaniam describes how school librarians and researchers have gathered evidence of their impact on reading and writing, but not, yet, within the STEM discipline. The NGSS coupled with AASL and ACRL standards, then, provide a robust framework for researching information literacy in the context of STEM disciplines. There is a blue ocean, if you will, of potential research from kindergarten through the university experience, in all areas of evidence for, in, and of practice. So, as a final exhortation to the sci-tech librarian reader, I hope this column provides some structure for and the genesis of ideas for seeking out opportunities to engage with the K-12 librarian/STEM educator community, improving student outcomes and increasing recognition of the role of information within the STEM disciplines. Take the opportunity to connect with your local high school, or interact with the STEM education faculty on your campus, to propose research projects aimed at exploring some of these information literacy topics, or even just have conversations to better understand their conceptualization of the Science and Engineering Practices or other aspects of the NGSS. Breaking down the barriers between STEM and IL educators will yield better outcomes for students and a more coherent, integrated approach for teaching students.

References

[AASL] American Association of School Librarians. 2007. Standards for the 21st Century Learner. Chicago: American Library Association. Available: http://www.ala.org/aasl/standards/learning

[AASL] American Association of School Librarians. 2015. Correlations between the AASL Standards for the 21st Century Learner and the Next Generation Science Standards. Chicago: American Library Association. Available: http://www.ala.org/aasl/sites/ala.org.aasl/files/content/guidelinesandstandards/ngss/NextGen_AASL_by_Grade.pdf

AASL and AECT. 1998. Information Literacy Standards for Student Learning. Chicago: American Library Association.

[ACRL] Association of College and Research Libraries. 2000. Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. Chicago: ALA. Available: http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/standards/standards.pdf

[ACRL] Association of College and Research Libraries. 2015. Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Chicago: American Library Association. Available: http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/issues/infolit/Framework_ILHE.pdf

Farmer, L. 2014. How AASL Learning Standards Inform ACRL's Information Literacy Framework. Paper presented at: IFLA WLIC 2014 - Lyon - Libraries, Citizens, Societies: Confluence for Knowledge in Session 72 - Committee on Standards; 16-22 August 2014, Lyon, France. http://library.ifla.org/id/eprint/831

NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards. Appendix F. Washington DC: National Academies. Available: https://www.nextgenscience.org/sites/default/files/Appendix%20F%20%20Science%20and%20Engineering%20Practices%20in%20the%20NGSS%20-%20FINAL%20060513.pdf

[NRC] National Research Council. 2012. Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. Washington DC: National Academies. DOI: 10.17226/13165

Ratzer, M.B. 2014. Opportunity knocks: Inquiry, the new national social studies and science standards, and you. Knowledge Quest 43(2): 64-70. Available: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1045948.pdf

Subramaniam, M. 2015. New territory for school library research: Let the data speak. Knowledge Quest. 43(3): 16-19. Available: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1049033.pdf

Todd, R.J. 2008. A question of evidence. Knowledge Quest 37 (2): 16-21.

| Previous | Contents | Next |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.