| URLs in this document have been updated. Links enclosed in {curly brackets} have been changed. If a replacement link was located, the new URL was added and the link is active; if a new site could not be identified, the broken link was removed. |

Gauging Workplace Readiness: Assessing the Information Needs of Engineering Co-op Students

Jon Jeffryes

Biomedical, Civil, and Mechanical Engineering Librarian

jeffryes@umn.edu

Meghan Lafferty

Chemistry, Chemical Engineering, & Materials Science Librarian

mlaffert@umn.edu

Science & Engineering Library

University of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Abstract

Librarians at the Science and Engineering Library at the University of Minnesota surveyed engineering students participating in a work placement as part of the cooperative education program. The survey asked about students' on-the-job information usage, comfort level accessing different types of engineering literature, and experience learning to use specific resources. All respondents indicated having to find some sort of information during their work placement. Industry standards and books had particularly high usage. A variety of levels of comfort and history of instruction were also reported. The goal of this study was to get a better idea of the practical information needs that undergraduate engineering students could expect to encounter in the workplace and better tailor our information literacy instruction to meet those needs in the future. These findings will further strengthen our case for curriculum integration in future conversations with engineering faculty.

Introduction

In Spring 2010 the Science & Engineering Library at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities conducted a survey of engineering students enrolled in a work placement through the cooperative education program. In this program, students work full time in a professional engineering work setting and earn credit towards the undergraduate engineering degree. The survey asked students to share their information seeking experiences while on the job. The findings provide a current snapshot of the information seeking environment in the engineering profession and inform the librarians' information literacy instruction.

Literature Review

One of the chief assumptions is that the work students do during co-op experiences is comparable to what they will do as early career engineers. There is precedent for this assumption in the work of Gardner and Motschenbacher and their exploration of the work experiences of recent engineering graduates (1993 p. 16-17). A corollary assumption is that it is possible to determine student preparedness for workplace information seeking on the basis of co-op experiences. Baber and Fortenberry's literature review supports these ideas when they refer to co-op experiences as the "best place" to assess how well students have learned how to be engineers (2008 p.4).

The significant role that information retrieval and evaluation skills play in engineering is well documented. A number of authors have reported that sizeable portions of engineers' workdays are devoted to information-related tasks (Allard, Levine, & Tenopir 2009; Robinson 2010; Strouse & Pollock 2009). While the specific amounts of time varied due to factors like differences in the authors' definitions of information seeking and the populations studied, information seeking is undeniably important to the practice of engineering. Davis, Beyerlein, and Davis described roles that professional engineers take on through their careers. Information seeking and evaluation skills are important for five of the ten roles described: Analyst, Problem-Solver, Designer, Researcher, and Communicator (2006 p.441).

The literature frequently addresses the importance of integrating information literacy skills into the engineering curriculum, particularly to be more attractive to employers (Amekudzi, Li, & Meyer 2010; Andrews & Patil 2007; De Lange 2000; Roberts & Bhatt 2007; Rodrigues 2001; Scaramozzino 2010). However, little has been written specifically on information seeking behavior and information literacy skills in relation to co-operative education, although it is often addressed implicitly. For example, the literature consistently describes communication as a top-ranked non-technical, or soft, skill for engineers; finding and using engineering information resources can arguably be considered one aspect of that skill set (Kreth 2000; Lappalainen 2009; Straub 1990). Cathy Costa's examination of the use of online information resources by students in economics, finance, and marketing co-ops at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University is the closest precedent for this study (2009). This project's goals are similar to Costa's, improving instruction and increasing student learning (2009 p.37). The scope diverges from that study in that it is both narrower in focusing solely on engineers and broader in its interest in students' holistic co-op information seeking experiences.

Methods

We surveyed the 42 students participating in the co-operative education program at the University of Minnesota's College of Science and Engineering during the spring semester of 2010. In order to secure departmental cooperation early on, we contacted co-op coordinators for the six engineering departments offering co-op programs (Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics, Civil Engineering, Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Computer Science, Electrical Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering) several months before administering the survey. We requested that the coordinators send out the survey on our behalf and encourage students to complete it. All except for the Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics department responded, all positively.

We chose UMSurvey, a local implementation of the open-source survey software LimeSurvey, to host the questionnaire and responses because of its accessibility to University-authenticated users, data security, and privacy. We drafted survey questions and vetted them with library colleagues, several engineering students with previous co-op experience, co-op coordinators, and a campus survey consultant. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board determined that the survey was exempt from further review. The survey asked all students to identify their information seeking experiences in the workplace and the sources they used (see Appendix I). The remainder of the survey focused on types of information resources. Students only saw questions about their comfort level and prior training in finding the materials they reported using on the job. Demographic questions were at the end of the survey.

Co-op coordinators sent an e-mail inviting students to take the survey three weeks before the end of the spring semester. We chose this time because students would have completed a significant portion of their co-op experience but still be on the job in the hope that it would lead to more accurate responses. We intentionally emphasized the brevity of the survey in the introductory e-mail. We offered no remuneration or reward, but stressed that the findings would help improve library support for the co-op programs. The survey remained open until the end of the semester, providing students the flexibility to answer at their convenience. A second e-mail sent a week before the survey closed reminded students to complete the survey. We subsequently analyzed combinations of demographic variables and student responses, looking for trends, particularly related to ease of finding different types of information.

After reviewing survey responses, we held short, informal follow-up interviews with five Spring 2010 co-op students the following spring. Some interviews were conducted in person and others by phone. The goal was fleshing out our understanding of the context of their responses. There were three questions:

- We want to get an idea of how information seeking assignments were given on the job. When you were asked to find information, were you asked to find information on a topic (e.g., find standards on ball bearings) or to locate a specific item (look at ISO 5464)?

- Was information seeking usually directed or self-instigated?

- Did you have to discover information seeking resources (web sites, databases) yourself or were you directed to look at specific individual resources?

Results

Of the 42 students who received the survey, 36 completed it, an 86% response rate. The majors and years in school of the respondents are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1: Demographic information by year in school

| Year | # of Students | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sophomore | 1 | 3% |

| Junior | 11 | 31% |

| Senior | 20 | 56% |

| Graduate student | 1 | 3% |

| Other | 3 | 8% |

| TOTAL | 36 |

Table 2: Demographic information by major(s)

| Major | # of Students | % |

|---|---|---|

| Civil engineering | 4 | 11% |

| Computer science | 1 | 3% |

| Electrical engineering | 3 | 8% |

| Mechanical engineering | 28 | 76% |

| Other | 1 | 3% |

| TOTAL | 37 |

Two-thirds of the students reported no previous experience in a similar applied engineering environment such as an internship or working in a professor's lab. All students with previous experience, most commonly an internship (17%), were upper level students or graduates, and all but one were Mechanical Engineering majors. When asked about information-related workplace support, 17% had access to either a library or librarian or both. Eighty six percent had Internet access and 64% had access to a company intranet.

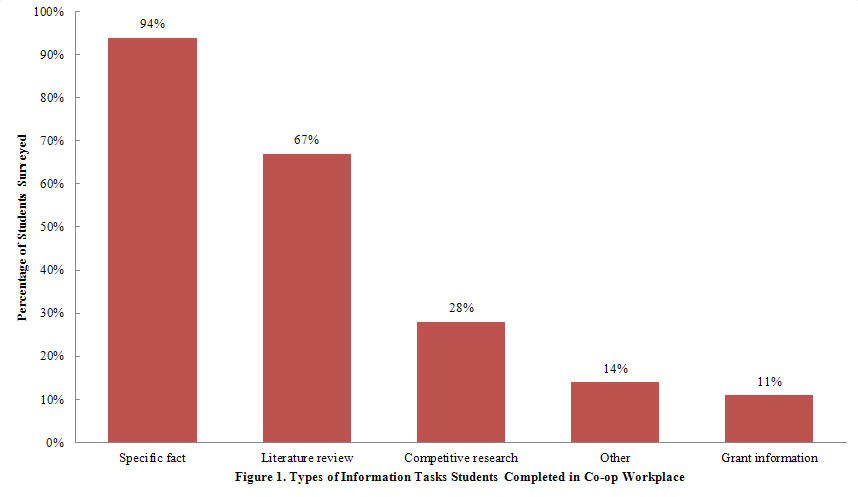

Respondents indicated which of five types of information-related tasks employers had asked them to complete during their co-op work placement: competitive research, grant information, literature review, specific fact, or other (Figure 1). Every student reported performing at least one such task, and 75% performed more than one. Overall, finding a specific fact (e.g., material property data) was the most widely reported task; almost all the students reported experiencing this type of information need at least once. A substantial number searched for information for a literature review, and a sizeable minority assisted with competitive research. Responses for "other" types of information seeking experience included "test method development," "finding information in a county archives," and "looking for as-builts and shop drawings."

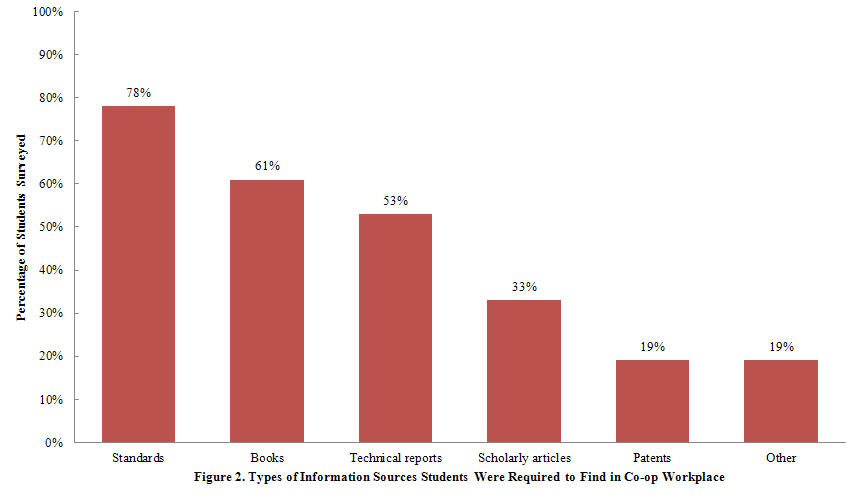

In addition to the tasks completed, students reported on which of five types of engineering literature they consulted to complete those tasks. Industry standards (78%) were the most common response, followed by books, and technical reports (Figure 2). Some of the "other" responses students gave included catalogs, vendor information, and web resources. Two students had not needed to use any of the resources listed.

For each type of resource, we asked students:

- How often they had used it prior to the co-op experience

- What year in school they were when they first learned to use it

- Who taught them to use it

- How easy they found it to use

Over half the students who used standards and patents during their co-op reported no previous experience finding them. Technical reports were new to 37% of respondents. Books and journals were familiar to nearly all.

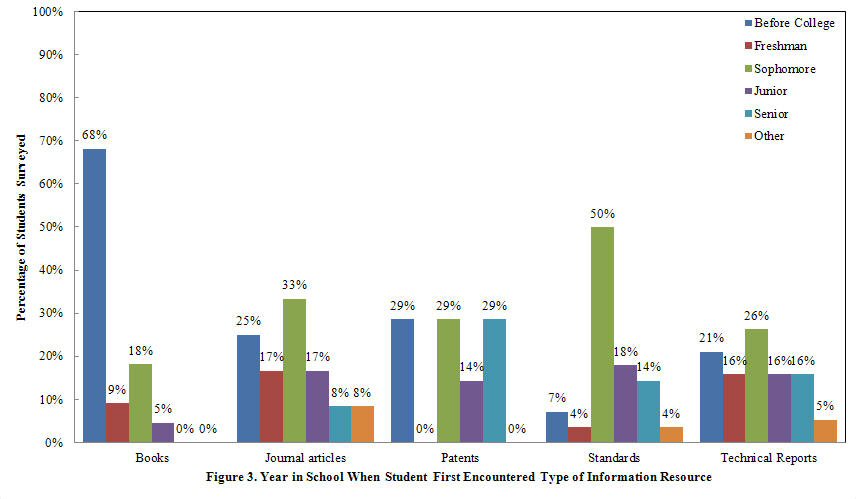

For all resources other than books, the highest percentage of respondents had learned to find them during their sophomore year of college (Figure 3). Nearly 70% of the students who used books in the workplace had learned to find them before college. Only 5% of students learned to find books during their junior year and none during their senior year or later. Across all the information resource types, sophomore year comprised 33% of all responses, followed closely by before college with 30%.

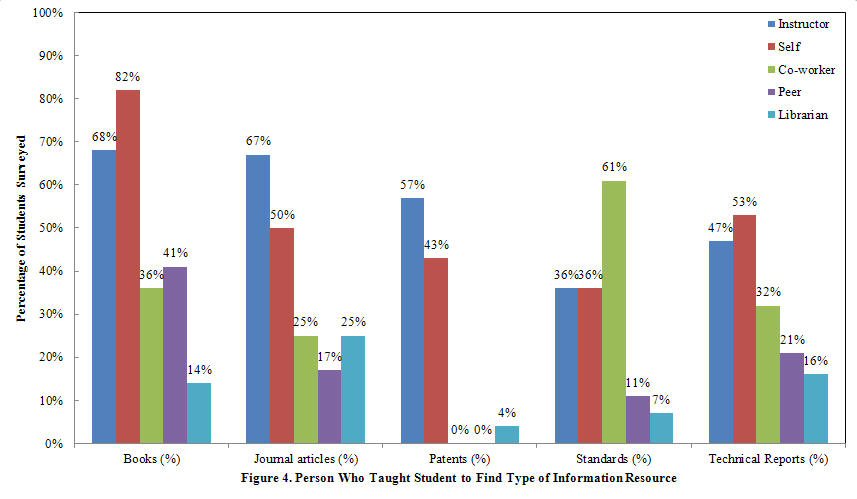

In answering who had taught a student to use a given resource, students had the following options (Figure 4):

- class instructors

- on their own

- a peer

- a co-op supervisor or co-worker

- a University of Minnesota librarian

Respondents could indicate multiple answers. We excluded a sixth option from the results ("during a directed research/UROP [Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program] experience [with a faculty member]") since no students selected that answer. In most categories, the greatest number of students learned about information resources either from an instructor or on their own. Standards were the only exception, as students indicated that co-workers were most likely to have taught them. No students credited either peers or co-workers for helping them learn to find patents. For each resource, at least one student had learned about it from a librarian.

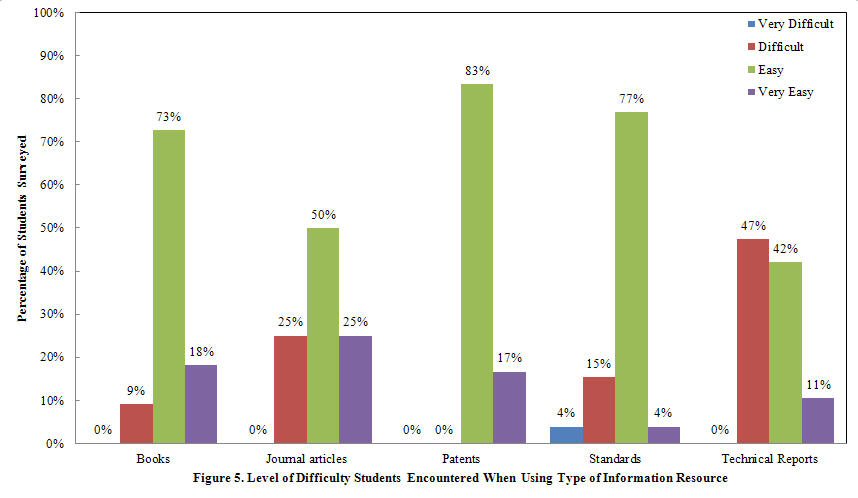

Respondents rated the level of difficulty they experienced finding resources during the co-op placement using a Likert-type scale that spanned from very easy to very difficult (Figure 5). We asked students about comfort as opposed to skill-level because we believed students' answers would be more accurate. In every case except for technical reports, at least half of the students considered a resource easy to find. Of the 19 students who had to find technical reports, 47% described the task as difficult; this result was the one case in which the number of students reporting a resource as difficult to find was greater than those reporting it to be easy. An equal number of students described finding journal articles as difficult and very easy. On the other end of the spectrum, nearly all of the students required to find books during their co-op placement found it either easy or very easy, and no students reported patents as being difficult or very difficult to find. Standards were the only literature type that any students described as being very difficult to find.

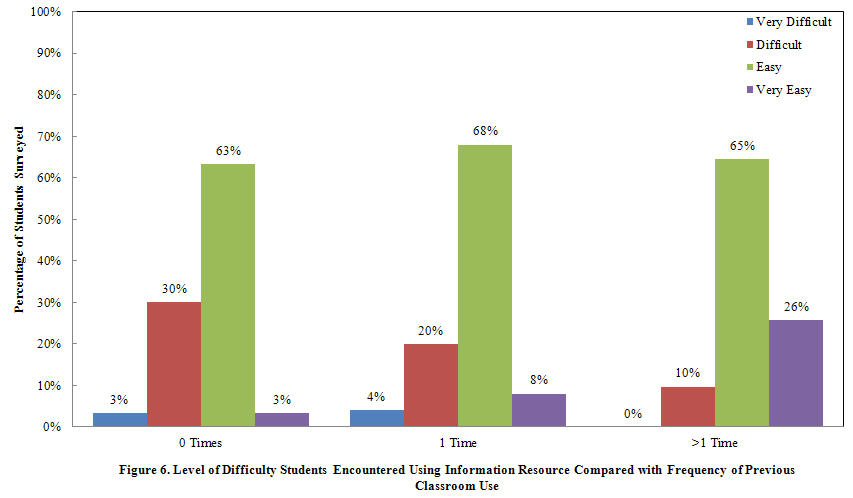

Figure 6 shows the comparison between how difficult students found the task of locating a type of literature with how often they needed to find it prior to their co-op experience. As students gained familiarity with a resource, they were less likely to report it being difficult to find and more likely to report that it was very easy to find. There was no clear trend in the frequency with which students reported using a resource as easy to find in comparison with their previous experience. In the two instances where a student described a resource as very difficult to access, neither had needed to find it more than once previously.

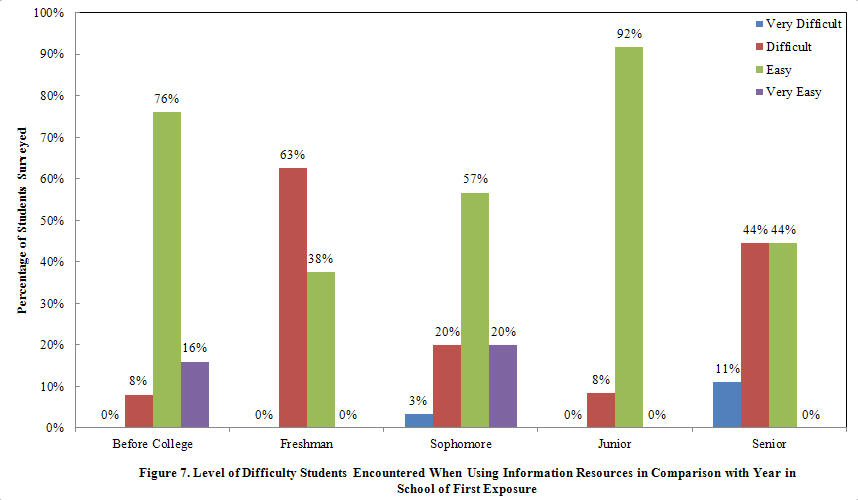

Another variable we looked at in conjunction with the ease reported of using information was the year in school when students recalled learning how to find a particular literature type (Figure 7). The majority of students who learned to use a resource as freshmen described finding the same resource as difficult during their co-op, in contrast with students who learned about an information type later in their academic career and indicated less difficulty with the information source during their co-op. The number of students reporting resources as difficult to find decreases as the year of introduction proceeds from freshman to junior year while the number of "easy" responses increases over that same period. For both "easy" and "difficult," neither "before college" nor "senior" follows the same pattern. All "very easy" responses are concentrated in the "before college" and "sophomore" categories.

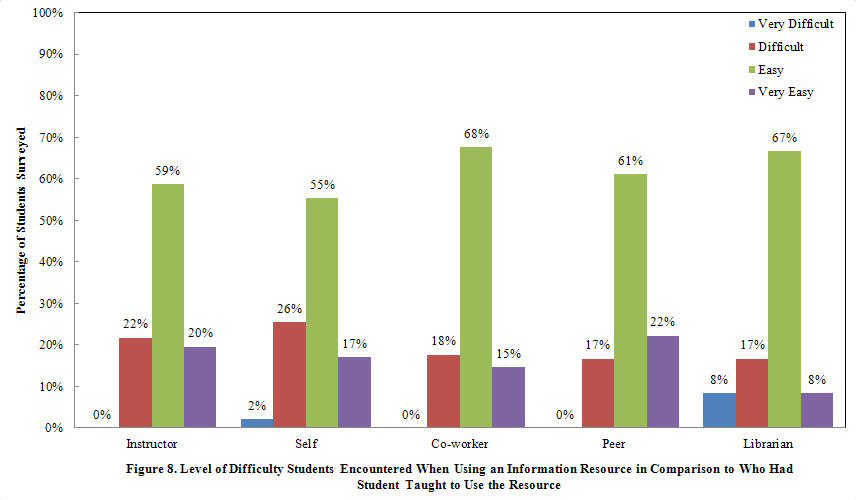

Finally, we compared students' comfort finding different literature types with who had taught the students to find that type of literature (Figure 8). Instructors and the students themselves were the primary source of instruction. Students who had learned to find a particular resource on their own reported the greatest amount of difficulty.

The follow-up conversations revealed co-op experiences that differed dramatically depending on firm size and type of engineering. The students' responses highlighted the idiosyncratic nature of their placement sites. Each student who participated in a follow-up interview described a unique mixture of self-directed and guided research questions that ranged from general topic searching to very specific known items.

Discussion

The fact that every student reported the need to find at least one type of information during their co-op experience is consistent with previous studies on engineers' information behavior and illustrates the importance of this skill set to the practicing engineer (Allard et al. 2009; Robinson 2010; Strouse & Pollock 2009). Given the pronounced role of information seeking in engineers' work, it was surprising that only 17% of the co-op students worked in companies with a library/information center or a librarian. Numbers that low suggest that students are likely to lack library support upon entering the workplace. This is much lower than what Napp found in a survey of the 500 most profitable engineering firms where approximately one-quarter had a librarian and 82% had a library (2004). The difference between our results and Napp's could be due to a combination of accelerated corporate downsizing due to the recession in combination with ever greater quantities of information becoming available online since 2004. Company size may also have been a factor; Napp's study found that firms without degreed librarians were, on average, ~2½ times smaller than those that did have them. Since the survey did not ask for information like company size, we can only speculate on its role in this study. Regardless of why so few of the students had or were aware of access to a library or librarian, the fact that most did not highlights the necessity of graduates being information-savvy as they move into the working world.

One way the results can help tailor instruction to student needs is with respect to the types of resources students needed at their work sites. Unsurprisingly, given how many students were already familiar with books when they began college, students were most comfortable with books as sources of information. Although more students worked with industry standards than any other type of literature during their co-op experiences, over half had no previous experience searching for them, and it was the only resource any students categorized as "Very Difficult" to find. The importance of standards and technical reports for the co-op students is a reminder to academic librarians not to overemphasize books and journal articles when working with engineering classes and students. Additionally, students' "Other" responses (e.g., vendor web sites) provide a more accurate map of their information universes.

It was heartening that the more experience students had with a resource, the more likely they were to report it being easy to find. However, it is unclear why students reported such difficulty with resources they had learned to find during their first year of college. Perhaps it was due to not using the skills since first learning them. Without information like the context in which students were exposed to resources, it is difficult to say.

The sophomore year stood out as the point when many students had been exposed to the engineering literature beyond books. A conversation with a mechanical engineering student helped us connect this observation with ME 2011: Introduction to Engineering, a required course for Mechanical Engineering majors. The class introduces students to the ways that mechanical engineers practice design and communicate and the tools they use for both in a very hands-on way (ME Course Catalog 2012). There is a long history of librarians working with the design classes mechanical engineering students take in their senior year. This class is a good entry point even earlier in the students' academic careers.

Students most often described finding different types of information as easy. We surmise that this result was affected in part by two phenomena: self-assessment inflation and social desirability bias. According to competency theory, novices are often unaware of what they do not know and tend to overstate their ability (Kruger & Dunning 1999). This has been demonstrated in a number of areas, including information literacy, and we believe that it was at play among the students we surveyed (Gross and Latham 2007; 2009). Social desirability bias entails responding to questions so as to seem intelligent or to embody other positive traits (Sapsford 2007). We doubt it plays as much of a role as students' tendency to have an inflated sense of their skill-level in this instance, but we cannot discount it entirely. These two factors make any student characterization of resources as difficult to find stand out even more markedly.

Most students learned to use resources from an instructor or on their own. The role of instructors was greater than anticipated as engineers are reputed to be very independent. We had expected that the students would primarily be self-reliant or look to peers. In addition to our own experiences as liaisons to engineering departments, there is evidence in the literature that "engineers tend to rely on their own information and on colleagues before the library and other internal sources" (Allard, Levine, & Tenopir 2009 p. 444). It is possible that instructors play a larger than average role in this particular mechanical engineering department.

There was less demographic diversity within the survey population than expected. The survey population was small and, as noted, almost entirely Mechanical Engineering majors. Some results may be more a function of the nature of the mechanical engineering discipline and the department's curricular focus. The results are also colored by the variety of co-op environments. Sizes, available resources, and cultures can differ greatly, and a student's experience may have a lot to do with one company's idiosyncrasies. Also, as Bailey said, cooperative assignments offer a mere "snapshot" of the engineering workplace (2007 p.666). We would need a far larger group of respondents from many schools working at a wide variety of firms in order to discern a more accurate "big picture."

The survey was not without its flaws. Upon examining responses, it was apparent that there was more room for ambiguity in the survey questions than anticipated. It was unclear whether students' understanding of "learning to use a resource" was the same as ours. We were confused by the fact that some students who had not previously used a given resource for a class assignment had learned to find that resource during an earlier year in school than their current one. Our guess is that those students had learned to use those resources in a non-classroom setting like an internship and had not used them for assignments. Defining what we mean by words like "use" and "find" in the survey would help ensure our understanding was more closely aligned with that of students.

Conclusions

When working with scientists and engineers, it is vital to have data to support claims about the need for information literacy instruction. Our study found that all co-op students were expected to find information in their work placements. What students had most frequently been taught to find was not necessarily what they most often needed to find during their co-op experience. Students who taught themselves how to find a particular type of information were more likely to describe that experience as "difficult."

We believe that successful graduates need strong information-related skills, preferably beginning early in their undergraduate careers. Librarians as information experts are well-placed to work with instructors in providing systematic instruction in how to locate and evaluate information. The instruction need not be onerous nor further bloat an already full curriculum. Taking advantage of opportunities to make use of the literature in the classroom and lab work would not require overhauling the core curriculum. It could be implemented through more intentional assignments or working with librarians to create short and effective online tutorials to give students guidance when they need it.

This research is more of a case study. We would be very interested to conduct further research with co-op students from multiple institutions and engineering disciplines. A larger and more diverse population could help tease out what findings were specific to our institution and the mechanical engineering discipline and what is more broadly applicable.

References

Allard, S., Levine, K.J., & Tenopir, C. 2009. Design engineers and technical professionals at work: pbserving information usage in the workplace. Journal of the American Society for Information Science & Technology 60(3):443-454.

Amekudzi, A.A., Li, L., & Meyer, M. 2010. Cultivating research and information skills in civil engineering undergraduate students. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice 136(1):24-29. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1052-3928(2010)136:1(24)

Andrews, T., & Patil, R. 2007. Information literacy for first-year students: an embedded curriculum approach. European Journal of Engineering Education 32(3):253-259.

Baber, T., & Fortenberry, N. 2008. The academic value of cooperative education: a literature review. 2008 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, June 22, 2008 - June 24. [Internet]. [Cited April 12, 2012]. Available from: {https://peer.asee.org/the-academic-value-of-cooperative-education-a-literature-review.pdf}

Bailey, R. 2007. Effects of industrial experience and coursework during sophomore and junior years on student learning of engineering design. Journal of Mechanical Design, Transactions of the ASME 129(7):662-667.

Costa, C. 2009. Use of online information resources by RMIT University economics, finance, and marketing students participating in a cooperative education program. Australian Academic & Research Libraries 40(1): 36-49.

Davis, D.C., Beyerlein, S.W., & Davis, I.T. 2006. Deriving design course learning outcomes from a professional profile. International Journal of Engineering Education 22(3):439-46.

De Lange, G. 2000. The identification of the most important non-technical skills required by entry level engineering students when they assume employment. The Journal of Cooperative Education 35(2):21-32.

Gardner, P.D. and Motschenbacher, G. 1993. More Alike than Different: Early Work Experiences of Co-op and Non Co-op Engineers. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University, Collegiate Employment Research.

Gross, M., & Latham, D. 2007. Attaining information literacy: An investigation of the relationship between skill level, self-estimates of skill, and library anxiety. Library & Information Science Research 29(3): 332-353.

Gross, M., & Latham, D. 2009. Undergraduate perceptions of information literacy: Defining, attaining, and self-assessing skills. College & Research Libraries 70(4): 336-350.

Kreth, M.L. 2000. Survey of the co-op writing experiences of recent engineering graduates. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 43(2): 137-152.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. 1999. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77(6): 1121-1134. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Lappalainen, P. 2009. Communication as part of the engineering skills set. European Journal of Engineering Education 34(2): 123-129.

Napp, J.B. 2004. Survey of library services at Engineering News Record's top 500 design firms: Implications for engineering education. Journal of Engineering Education 93(3): 247-252.

Roberts, J.C., & Bhatt, J. 2007. Innovative approaches to information literacy instruction for engineering undergraduates at Drexel University. European Journal of Engineering Education 32(3): 243-251.

Robinson, M.A. 2010. An empirical analysis of engineers' information behaviors. Journal of the American Society for Information Science & Technology 61(4): 640-658.

Rodrigues, R.J. 2001. Industry expectations of the new engineer. Science and Technology Libraries 19(3-4): 179-188.

Sapsford, R. 2007. Measurement: principles. In Survey Research. London: Sage Publications, Ltd. p. 101-108.

Scaramozzino, J.M. 2010. Integrating STEM information competencies into an undergraduate curriculum. Journal of Library Administration 50(4): 315-333.

Straub, R. 1993. Engineering students perceptions of non-technical employment qualities. The Journal of Cooperative Education 27: 45-55.

Strouse, R., & Pollock, D. 2009. Understanding Scientists' and Engineers' Information Use Habits, Preferences, and Satisfaction. Burlingame, CA: Outsell, Inc.

University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. 2012. Mechanical Engineering Catalog. [Internet]. [Cited March 1, 2012]. Available from http://onestop2.umn.edu/courses/courses.jsp?campus=UMNTC&designator=ME

Appendix

Survey Questions (PDF)

| Previous | Contents | Next |