| URLs in this document have been updated. Links enclosed in {curly brackets} have been changed. If a replacement link was located, the new URL was added and the link is active; if a new site could not be identified, the broken link was removed. |

Database Reviews and Reports

Scopus

Physical Sciences Resource Librarian

Library of Science & Medicine

Rutgers University

Piscataway, New Jersey

dess@rci.rutgers.edu

Introduction

Scopus, a product of Elsevier Publishing Co., was commercially launched in November 2004 as "the world's largest abstract and indexing database," reputedly spanning the full spectrum of science-technology-medicine (STM) literature plus more limited coverage of the social sciences. In addition, Scopus offers citation searching, an important feature that until recently has been the exclusive province of ISI's Web of Science. Earlier reviews (Deis and Goodman 2005; Jacso 2004; Jacso 2005; LaGuardia 2005) provided extensive initial evaluations of Scopus with particular emphasis on comparisons with Web of Science, in which various problem areas and limitations were identified for further development and improvement by Scopus. A later critique by Fingerman (2005) offered additional helpful observations.A Scopus web site (Scopus Info) provides a wealth of descriptive details about the product, including an account of the "User-Centered Design" approach that was adopted, which enlisted the collaborative efforts of over 300 researchers world-wide at 21 different institutions for extensive product testing and feedback.

Database Size and Time Span

Scopus currently contains nearly 27,000,000 document entries extending back to the mid-1960s. Whether or not this number justifies its claim to be the largest such database is debatable when compared with other reigning giants such as Web of Science or SciFinder. However, both Web of Science and SciFinder cover much longer time spans than Scopus, so any such size comparisons must be more carefully qualified. About half of the Scopus records fall in the period 1994 to date, with the remainder extending back through 1963 (a peculiar tail-end of 317 entries straggles all the way back to 1902, but no rationale could be discovered for inclusion of this material). Annual growth in the literature recorded in Scopus over the past several years increases from about 726,000 entries added in 1993 to 1.46 million in 2004, or nearly double the earlier total. This content was obtained from some 14,200 source titles (primarily journals, but the database also includes books and various kinds of reports) produced by more than 4,000 international publishers. Elsevier also includes some 531 open access journals in these totals, and further notes that over 60% of the titles originate from non-U.S. sources. Items in the latter category are included, regardless of the language of the article, provided that an English language abstract is available.

Source materials are listed in a browsable index easily accessed via a prominently labeled tab located at the top of the search interface page. Additional information on open source materials can be accessed via a link provided in the Scopus Info web site.

Content

Subject Coverage: Elsevier provides the following break-down of subject coverage in Scopus, by the number of source titles that are utilized [Scopus Info web site]:

- Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics and Engineering: 4,500 titles

- Life and Health Sciences: 5,900 titles (100% Medline coverage)

- Social Sciences, Psychology and Economics: 2,700 titles

- Biological, Agricultural and Environmental Sciences: 2,500 titles

- General Sciences: 50 titles

Unfortunately, this rather arbitrary lumping together of different disciplines obscures some important strengths and weaknesses of Scopus.

A more revealing picture of the range of subject matter covered by Scopus is illustrated by the following summary of the number of documents recorded in each category, as determined by actual test searches and utilization of Scopus' own subject classification scheme applicable to the answer sets:

- Health 14.3 million documents

- Life sciences 11.0

- Engineering 8.5

- Agricultural & Biological Sciences 3.6

- Earth & Environmental Sciences 1.9

- Chemistry 1.3

- Physics 0.59

- Social Science 0.29

- Mathematics 0.26

- Psychology 0.23

- Economics, Business, Management 0.22

The total for all categories comes to 42.2 million documents, which is 15.3 million higher than the document count for the entire database. However, this discrepancy reflects double counting (or more) of documents whose subject matter falls into more than one subject category. The most important observation to be noted from these figures, however, is the heavy concentration in the health-life-and-engineering subject categories as compared with the much more limited coverage in the areas of agricultural science, earth science, and chemistry. By the same token, if we assume that the subject field assignments recorded by Scopus always accurately reflect the central focus of each publication, then coverage in the fields of physics, mathematics, and psychology is disturbingly low, and the social sciences and the business subject categories also have very lean representation in Scopus as compared, say, with Web of Science. Finally, in marked contrast with Web of Science, there is no content recorded in Scopus for the category of "arts and humanities". For comprehensive searches in the field of chemistry, SciFinder Scholar would still be the preferred choice; for physics, INSPEC; for psychology, PsycINFO; and Web of Science for interdisciplinary searches in STM subjects, the social sciences, or arts and humanities over longer time spans, especially where citation tracking is required for literature published prior to 1996.

Document Types: Scopus identifies 14 different document types. Not surprisingly, the top category is "article", numbering over 20 million entries, followed by "review" with 1.4 million entries, "letter" with 0.53 mill records, "note" at 0.41 million records, "editorial" at 0.27 million entries, and "short survey" with 0.24 mill records. The population of the remaining eight categories falls off rapidly but includes some decidedly interesting entries such as: "erratum" at 77.2 thousand, "conference review" at 36.9 thousand, and "books" at 20.0 thousand. Searches can be limited to any one or more of these categories if so desired, but for reasons detailed below, the results of imposing such restrictions must be viewed with caution.

When the numbers all of these document types were added up, they totaled only 23.1 million entries, which is about 3.8 million lower than the total content of the entire Scopus database (some 27 million records). Why this discrepancy? To explore this question further, a full database search was rerun and all 14 document categories were excluded, yielding a residual of some 3.8 million "unclassified" documents available for examination. A random spot check revealed that many were individually identified as articles, but for some reason they had not been swept into the proper document category by Scopus. Others were identified only with a DOI. Moreover, an apparent time dependency was discerned: nearly all of these unclassified entries occurred during the period 1966 through 1996. Finally, certain subject categories were more strongly affected than others: for example over 1.6 million "health" subject records fell into this group ; "engineering" records totaled 1.6 million entries; and "earth and environmental sciences" amounted to 663 thousand. These numbers represent records that would likely have been missed if the searcher had imposed the document type restriction to the "article" category.

Search Interface Overview

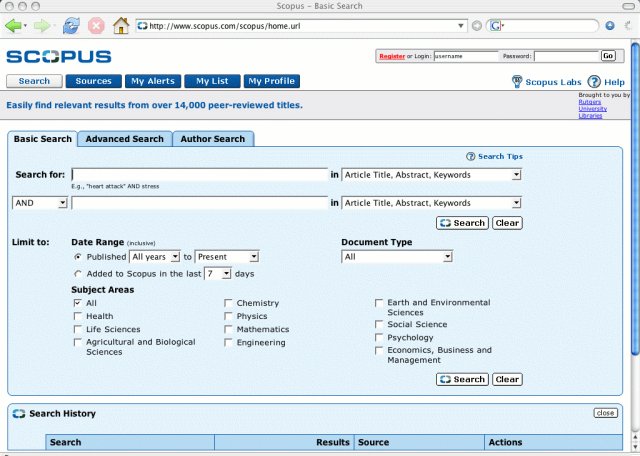

Scopus scores a solid hit with its eye-appealing and very user friendly search interface. (See Figure 1) Experienced searchers will feel comfortable with the clear design graphics that make it easy to construct searches with varying degrees of complexity. Newcomers or novice searchers can take advantage of numerous search aids that offer multiple levels of guidance about how best to conduct various types of searches. "Help" buttons located in the upper and lower corners of each web page provide ready access to an encyclopedic range of help topics. And a "Search Tips" button is positioned just above the standard dialog boxes providing the perplexed searcher further support to help deal with any questions that may arise. In addition to the usual index of help topics, new users can also take advantage of an online tutorial that provides a very helpful introduction to the use of Scopus. One must conclude that Elsevier has taken extraordinary efforts to make the Scopus search process as clear and easy to navigate as possible.

Search Options

Basic Search: This is the default search option that greets the user when Scopus is first opened, and the default search fields are "Article Title, Abstract, Keywords." However, the searcher can also change these fields, as desired, choosing from a list of 16 options via a pull-down menu that includes, for example, author(s), or source title, or article title, etc. Use of a second dialog box permits one to construct more complex searches that combine, for example, author/title searches, or keyword/source title searches, etc. Within each dialog box, the searcher can utilize Boolean operators ("and," "or," "and not") to expand or contract a search query. Truncation or wild cards (? for individual letters or * for zero or unlimited letter strings) can be used to provide greater scope and flexibility in searching. And still finer control of search strategies can be obtained through the use of proximity operators, e.g., cat pre/5 dog specifies that the word "cat" must precede the word "dog" by five or fewer intervening words; alternatively, the format cat w/5 dog would be used if word order was immaterial.

"Basic Search" also permits imposition of additional limits:

- By year or year ranges, or by latest seven-day update

- By document type, with 11 choices such as "article", or "review" or "letter", etc.

- By subject areas, with a menu of 12 choices such as "health", "life sciences", "chemistry", etc.

Use of the latter two limits poses potential problems for the searcher as explained earlier, and should be employed with caution (if at all!).

Advanced Search: Searchers wishing to construct more complex search strategies than would be possible via Basic Search, can try their hand with this option. However, be warned that the terminology required can be complex and the essential field names (well over 50 of them before we stopped counting) appear unnecessarily cumbersome in many cases (e.g., "authlastname" is the field code required for designating author's last name). A list of examples is provided to illustrate various ways one can utilize "Advanced Search", and they are helpful to the extent of demonstrating the attention to detail demanded of the user when formulating one of these sequences. Missing a crucial hyphen or inadvertently mistyping one of the longer field names will invalidate a search and yield zero retrievals.

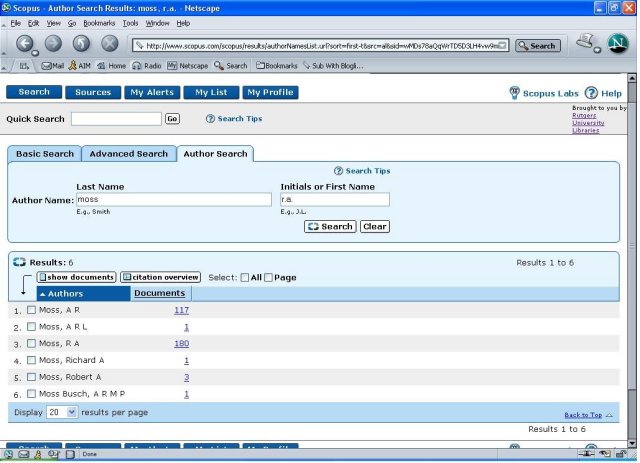

Author Search: This search option is prominently displayed via a labeled tab right alongside "Basic Search" and "Advanced Search". When Scopus was first introduced, the utility of this search mode was very limited because of the omission of an author name browse function. This lack of name browsability was especially frustrating when dealing with common names such as Smith or Jones or Wang, where use of first names or sets of name initials are essential to narrow a search. Apparently responding to user complaints, Elsevier subsequently upgraded the name search function in mid-December of 2005 so that it now permits name browsing. This change is part of a broader upgrade labeled "The Scopus Citation Tracker" which is fully described on the Scopus web site (Scopus Find Out). (The citation tracking aspects will be covered in a later section). The animated displays on the use of these upgrades are particularly well designed and helpful for new users.

As welcome as the introduction of the author name browse function is, users will need to remember that this function is restricted to name searches initiated in the "Author Search" field only and does not apply to author searches carried out in the "Basic Search" mode (i.e., via use of the pull down menu). However, users can copy and transfer full author names found in "Author Search" (including first names or initials) into the "Basic Search" or "Advanced Search" dialog boxes where they can be combined with other search terms to provide more tightly focused searches.

Presentation of Search Results

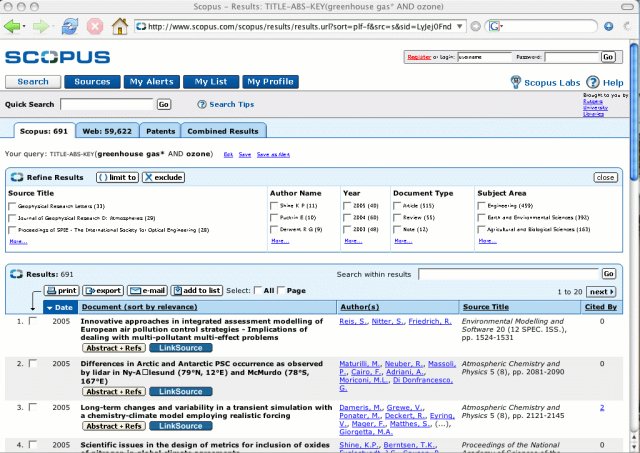

Display and organization of search results (answer sets) are outstanding in Scopus, probably the best of its kind currently offered by a commercial database. By way of illustration, a fairly straightforward search was run to obtain information on the following topic: the effect of green house gases on the ozone layer. The search strategy employed and the answer set retrieved is reproduced in Figure 2. It is immediately apparent that a cornucopia of information is summarized on each answer set screen. Starting with the three tabs at the top, the following overview of the search is summarized:

- Scopus yielded 690 hits

- Web retrievals (via Scirus search engine) totaled 465.

- Clicking on the "patent" tab revealed 4 hits (via linkage with Espacenet)

One disturbing finding for searchers to ponder: variability in the number of retrievals of web sources and patents varies wildly from day to day. This search was repeated several times over the course of a few days and while the Scopus retrievals remained constant at 690, web retrievals ranged from a high of 57,710 down to the number shown in Figure 2; and patent retrievals ranged from a high of 470 down to four.

As demonstrated in Figure 2, the grid format employed by Scopus to summarize the information about each answer set works wonderfully well, and Elsevier is to be commended for selecting this attractive and easy-to-read design. Bibliometric data about the answer set is organized into columns which identify each of five major categories of information, where entries are listed in rank order of the number of retrievals obtained for each of the following data fields: source title; author name; publication year; document type; subject type. Initially compressed into just a few lines, each of these categories can be expanded and individual authors or journals, for example, can be selected (or excluded) as a convenient way to zero in on specific areas of interest to the searcher.

The individual references retrieved are listed below the bibliometric summary section, in chronological order as the default mode, starting with the most recently published material. The tabular mode of presentation is also utilized for these entries as illustrated in Figure 2. Presentation of the bibliographic information about each reference in this standardized grid fashion makes it particularly easy on the eyes for quick scanning purposes. Answer sets can also be readily re-sorted, say, in alphabetical order of first authors, or by number of citations for each reference listed, or by publication year, etc.

Searchers are thus provided with tremendous flexibility in manipulating search results to suit their individual literature research needs. This is in marked contrast to the much more limited and restrictive sorting options offered by Web of Science. Finally, Scopus permits the option of searching within an answer set, using additional key words or even author names. Thus the 690 hits originally retrieved in the above example were reduced to 197 when the answer set was searched for the additional term "methane".

Specific references or entire blocks of answers can be easily transported to other systems via e-mail or moved into bibliographic management products such as RefWorks, ProCite, or End Note for storage and future utilization by the user. Buttons specifying these transport functions are conveniently positioned by Scopus right at the start of each set of the answers listed on any screen page.

Finally, search history is recorded back on the original search page, near the bottom of the page. Individual searches are cumulated and numbered and can be combined via Boolean operators, if so desired, for further search possibilities. One quirk of the system to keep in mind: searches that utilize the "search within" option are not recorded in history. This is a serious deficiency, one that we hope will be rectified by Elsevier in future upgrades of Scopus.

There are some additional caveats to be noted. For reasons that are not yet fully understood and which require further investigation, the number of answers retrieved in a search can vary depending on the entry order of the search terms. In the example described above, the following variations are illustrative:

- A search for "greenhouse gas*" (title/abs/kw) yielded 10,284 hits; a search within this answer set for "ozone" then retrieved 1,110 hits (rather than the 690 recorded earlier)

- A search for "ozone" (title/abs/kw) recovered 38,699 hits; a subsequent search of this answer set for "greenhouse gas*" retrieved 1,372 hits.

It is suspected that the reason for these apparent inconsistencies lies with the "search within" function which appears to search all fields, whereas on the starting search page the default search is limited to the title/abstract/keyword fields. Additional testing is required for a better understanding of this matter.

Citation Searching in Scopus

Citation searching is one of the most important functions offered by Scopus. Regrettably, Elsevier's decision to limit the reach of Scopus' citation backfile to the period 1996+ is a serious drawback for users seeking to understand the development of any given field of research whose roots extend farther back in time than that. In such cases one must employ other commercially available resources such as Web of Science, the pioneer in this field, but one that is increasingly challenged by databases that are more subject specialized, from other producers who have also added citation searching to their list of functionalities in recent years (e.g., SciFinder, Medline, Psycinfo, etc.). Nevertheless, if one keeps this time frame limitation in mind when using Scopus, and in cases where such limitation is acceptable, Scopus can prove to be a versatile and easy-to-use literature tracking tool.

As an extreme example of the limits to which Scopus could be stretched in conducting a citation search, the following test was conducted: a search was run in which the entire database was retrieved as an answer set, i.e., all 26.9 million records. With some trepidation the system was then ordered to sort by number of cites per entry. It is gratifying to report that this immense sorting operation took less than 10 seconds. This heroic performance must be considered as awesome and speaks volumes about the magnitude of the computing power that Elsevier has put at the disposal of Scopus users. This type of operation would be impossible with Web of Science, which imposes strict and relatively narrow limits on sorting operations. The Scopus citation search results (numbers of cites per publication) were then compared with citations retrieved for these same references via use of Web of Science and SciFinder Scholar (use of SciFinder Scholar was relevant because the subject matter of some of the more highly cited documents retrieved dealt with chemistry-related subjects). Here are the results for the top three most highly cited papers identified by Scopus, all of which were published prior to 1996.

| Scopus | Web of Science | SciFinder Scholar | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laemmli 1970 | 65,009 | >65,535 | 49,219 |

| Bradford 1976 | 53,804 | >65,535 | 44,915 |

| Chomczynski & Sacchi 1987 | 35,262 | 54,510 | 24,955 |

In every case Web of Science yielded higher numbers of cites than Scopus (in many cases thousands higher), by virtue of the fact that Web of Science citation records extend much farther back in time. One unexpected result, never before encountered with Web of Science, was the upper limit imposed on the number of citations retrieved: apparently 65,535 is the maximum number of citation retrievals permitted by Web of Science. This finding is more of a curiosity than indicative of a problem, since most Web of Science searches are orders of magnitude smaller than the example described. Finally, the SciFinder Scholar citation retrieval numbers were generally lower than both Web of Science and Scopus, but were also usually much closer to the latter than the former. This outcome was not unexpected since SciFinder Scholar focuses more narrowly on chemistry than the other two interdisciplinary databases and its current citation search backfile covers fewer years than Web of Science.

A substantially different picture emerges when citation searches are limited to literature published later than 1995. In this case, Scopus yielded a total of 11.9 million retrievals, which were then sorted by number of citations, as was done previously. Looking at the top 20 retrievals, the number of citations recorded for these references by Scopus ranged from a high of 14,992 down to 3,053 for number 20. These same 20 references were then searched in Web of Science for comparison purposes. In this comparison test the citation retrieval results for these two databases were much more closely matched:

- For this set of 20 articles, in total, Scopus retrieved 97,601 citations versus 96,435 for Web of Science, a difference of only 1166 or 1.2%, in favor of Scopus.

- Scopus retrieved more cites per article than Web of Science for 11 out of the 20 articles and fewer than Web of Science for the remaining nine.

- In most cases the differences were not large, ranging from a mere six to a maximum of 2102, with an average difference of +/- 303 (as compared with differences ranging into many thousands for articles published prior to 1996).

Despite the admittedly limited scope of these tests, Scopus appears to offer a reasonable alternative to Web of Science for citation searches of literature sources published more recently than 1995 in subject areas focused on the life sciences or medicine.

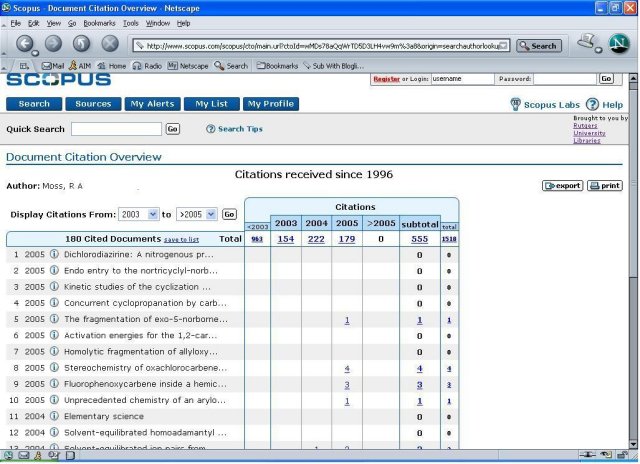

Presentation and Manipulation of Citation Data: The December 2005 upgrade noted above under "Author Search" also introduced several new options for displaying and utilizing citation data. Using the Scopus Citation Tracker function searchers can:

- Generate tabular displays of citations to the publications of any given author for a specific year or range of years extending back to 1996. (The results of an author search is shown in Figure 3; after selecting a specific author, the searcher then clicks on the button labeled "Citation Overview" to produce the tabular display shown in Figure 4).

- Produce tables summarizing the number of citations per year for specific articles of interest over one or more years ranging back to 1996.

- Subject the citing articles to further analysis that permits tracking the development of research trends over time.

The graphical-tabular format of these displays is certainly helpful in providing easy scanning of results although some of the more grandiose claims in the Elsevier web site elicit some reservations in the mind of the critical reviewer.

Cost Considerations

Scopus is marketed as an interdisciplinary STM database and despite the limitations and qualifications associated with this claim, as detailed in earlier sections, that places it squarely in competition with Web of Science, the trail blazer in this area and which has had the field to itself until now. This means that potential purchasers who have already subscribed to Web of Science are faced with three choices:

- Retain Web of Science and do not acquire Scopus

- Switch from Web of Science to Scopus

- Acquire both

Pricing now becomes a critical factor as prospective buyers consider the cost/benefit consequences of their decision. For the purposes of this review, however, a cost comparison between Scopus and Web of Science is nearly impossible to make with any degree of precision because pricing information is closely held by the database producers, and subscribers are normally bound to silence by confidentiality agreements. What is known in general terms is that pricing is a complex matter, tied to the size of the institution (FTE count), consortial discounts that are negotiated, and other factors as well. In their earlier review (Deis and Goodman 2005) estimated Web of Science costs ranging in excess of $100,000 per year for large institutions, down to "low five figures" for the smallest schools. The cost of Scopus was estimated at something in the range of 85-95% of the cost of Web of Science for the same institutions. With library budgets stagnant or even shrinking when compared with inflation trends, it is highly unlikely that any institution will be willing or able to afford both of these products. Therefore, the choice of which one to acquire will be determined by the kind of trade-offs of cost versus performance each institution is willing to make.

Conclusions

Scopus is a promising addition to the stable of workhorse databases now available to researchers in the STM subject categories, and its interdisciplinary content coupled with citation searching capability inevitably sets it up as a direct rival to Web of Science. Although definitive pricing information is not publicly available for these costly products, earlier estimates indicate a modest edge in favor of Scopus. However, prospective buyers must also factor in a host of performance and content factors to determine which of these products will better serve the needs of their user communities.

Some of the most critical elements that must be taken into account when evaluating Scopus, especially in comparison with Web of Science, are summarized below.

On the plus side, these Scopus features are particularly noteworthy:

- Outstanding visual graphics and search interface distinguish Scopus as very user friendly, both for entry of searches and viewing of answer sets.

- Scopus' citation searching feature is a particularly important functionality that expands the range of choices available to users for this research tool.

- Computing speeds are impressive. Waiting times for answers are negligible even for the largest data sets.

- Sort options for answer sets are broad, easy to use, and applicable even to very large answer sets.

- The bibliometric summaries provided with each answer set are a valuable bonus feature that can be further utilized to help characterize an answer set or refine a search strategy.

- Abundant "Help" files are provided and made easily accessible.

Regrettably, certain other aspects of Scopus are more problematic and users need to know about certain limitations inherent in the product as currently constituted. Some of the more troubling features requiring awareness on the part of the researcher and remedial action by Elsevier, are the following:

- In its present makeup, Scopus cannot be considered as a comprehensive repository of STM literature. Content is most heavily weighted in the health and life sciences, with less adequate subject coverage in the physical sciences, mathematics, psychology, and social sciences; and the area of business and marketing has essentially only token representation.

- Citation tracking is limited to the relatively narrow time span 1996+. This window of access is obviously too restrictive for searchers delving into subject areas with longer periods of historical development. Web of Science has a clear advantage on this feature.

- Certain technical aspects of the search options provided by Scopus need improvement or redesign:

- The "search within" function needs to define or specify which search fields it covers. Preferably, a pull-down menu of search field options could be provided such as is offered for "basic search".

- The "search within" searches need to be included in the search history.

- The "advanced search" function is too complex in its present form. A good starting point for revision would be to simplify some of the more cumbersome field names.

- The "document type" fields display some puzzling gaps that need to be corrected.

Scopus offers such a dazzling array of user friendly search options that one is tempted to overlook some of its more serious deficiencies. However, that would be a mistake. In its present form, Scopus can best be recommended for searchers interested primarily in the literature of the life sciences and medicine, over the period 1996+, which is the time span covered by citation tracking in Scopus. As search interests extend beyond these parameters, users will be less well served by Scopus (in terms of information retrieval and citation tracking) than by other commercially available databases in a comparable price range, especially Web of Science.

At this point, we can only hope that Elsevier will build on the existing foundation to expand both content and time span for this appealing new resource as well as to correct some of the technical deficiencies noted earlier.

References

Bradford, M. M. 1976. A Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram Quantities of Protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry 72 (1-2):248-254.Chomczynski, P. & Sacchi, N. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform extraction. Analytical Biochemistry 162(1):156-159.

Deis, L. F. & Goodman, D. 2005. Web of Science (2004 Version) and Scopus. The Charleston Advisor 6(3). [Online]. Available: {http://www.charlestonco.com/comp.cfm?id=43}[December 7, 2005].

Fingerman, S. 2005. Scopus: Profusion and Confusion. Online 29(2):36-38.

Jacso, P. 2005. As We May Search--Comparison of Major Features of the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar Citation-Based and Citation-Enhanced Databases. Current Science 89(9):1537-1547. [Online]. Available: {http://www.iisc.ernet.in/currsci/nov102005/1537.pdf} [December 7, 2005].

________. 2004. Scopus. Peter's Digital Reference Shelf, Thompson-Gale web site. [Online]. Available: {https://web.archive.org/web/20070105074206/http://www.gale.com/servlet/HTMLFileServlet?imprint=9999®ion=7&fileName=reference/archive/200409/scopus.html [December 7, 2005].

Laemmli, U.K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacterio phage. Nature 227(5259):680-685.

LaGuardia, C. 2005. E-Views and Reviews: Scopus vs Web of Science. Library Journal.com. [Online]. Available: {http://lj.libraryjournal.com/2005/01/technology/e-views-and-reviews-scopus-vs-web-of-science/} [December 7, 2005].

Scopus Info. [Online]. Available: http://info.scopus.com/ [December 7, 2005].

| Previous | Contents | Next |